DNA methylation in prokaryotes

Jan 31, 2020 21:42 · 1001 words · 5 minute read

Introduction

I was researching possible failure modes of plasmid transfection in e. coli, and I came across a post that mentioned DNA methylation as a possible problem. I had not dug into this before, and discovered that it is an entire field of study within biology. Before I realized how broad the topic was, I anticipated writing this blog post on DNA methylation; I then reduced its scope to only prokaryotes, though I will talk a little bit about how DNA methylation affects eukaryotic organisms as well in order to provide more context for what it does and how it works.

Basics of DNA Methylation

To understand what’s going on, I needed to draw from some of my organic chemistry knowledge. A “methyl” group is just a single carbon attached to the side of a chain of carbons. So when we say that something is “methylated”, we just mean that it had a CH3 molecule attached to it. Carbon likes to have 4 bonds, so the single carbon atom attaches itself to a larger thing, and brings its 3 Hydrogen friends along for the ride because that way the Carbon has 4 bonds.

In general, DNA methylation occurs on cytosine (the C part of DNA - remember G, T, C, A), so I’m going to focus on that. Methylation can also happen on Adenine (the A part of DNA - remember G, T, C, A), but it is not as well studied.

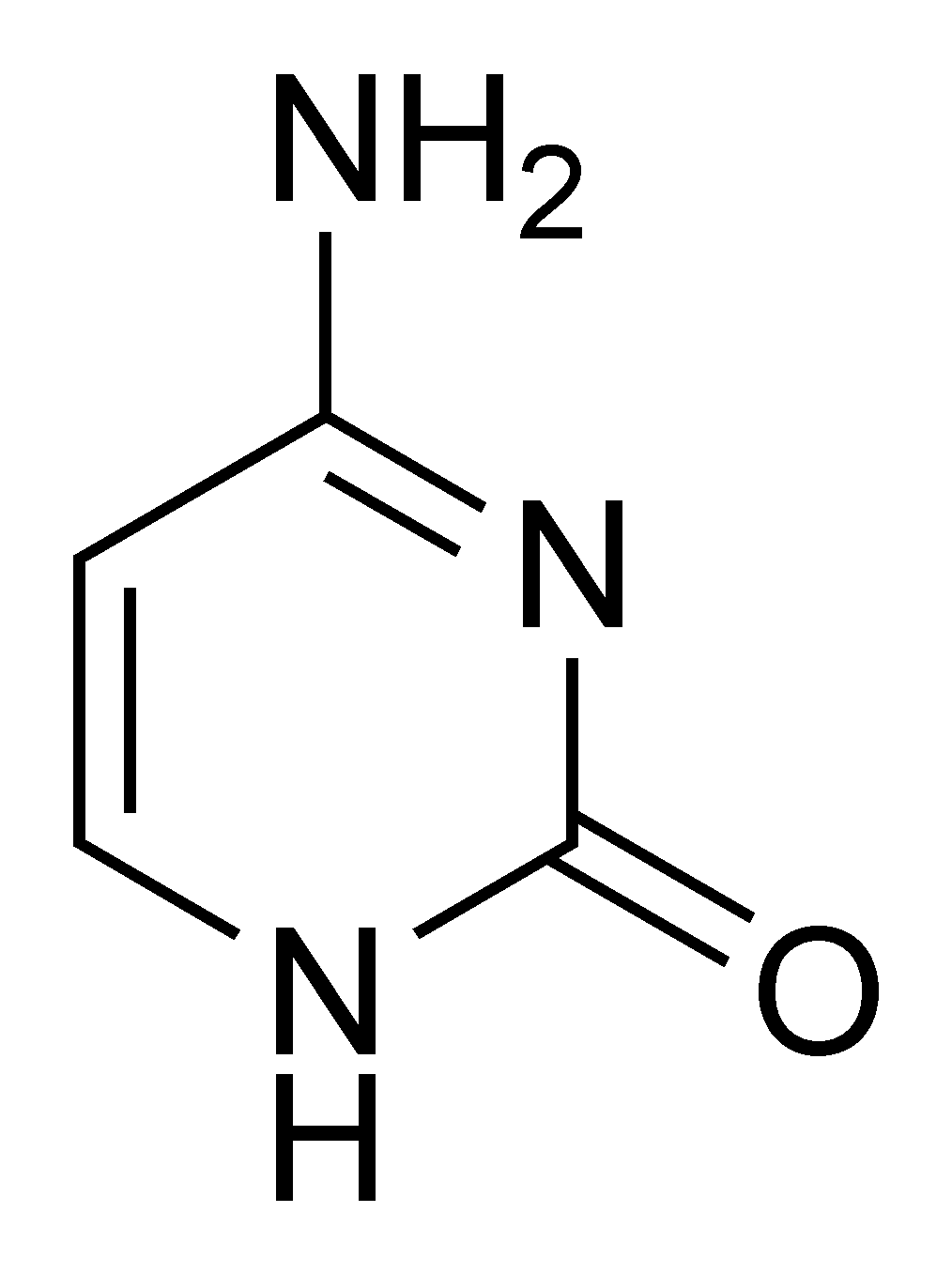

Each base in DNA is a relatively simple molecule, they all look similar to Cytosine:

Cytosine

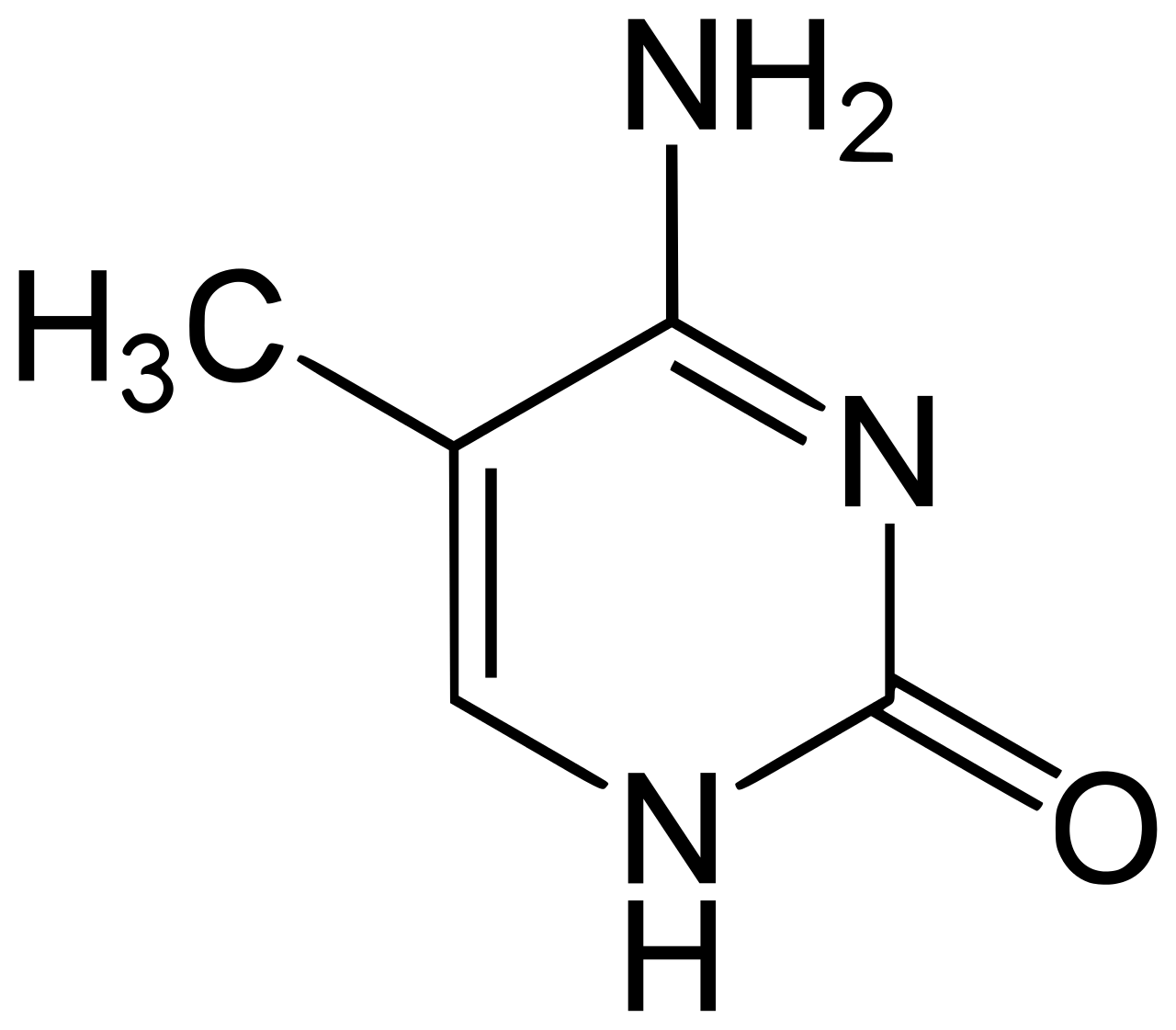

Each C represented in a genome has the molecular structure described in that image. When the cytosine is methylated, it turns into the following structure:

Methylated Cytosine (5-Methylcytosine)

If you’re not familiar with organic chemistry, the only difference is the extra line in the upper left of the molecule. That’s it!

Effects of Methylation

The effects of methylation are still being studied, and there is a substantial amount of research on epigenetics that is derived from the effects of methylation.

There are two primary effects of methylation

- Introducing mutations

- Protecting DNA

Introducing mutations

The process that I will be talking about here is called “deamination”. Though scientists often name things with lots of syllables, they are logical. Deamination is the process of a molecule losing an “amine”. “Amine” is a shorthand for “a nitrogen with 2 electrons on it which is bonded to 3 other ‘groups’”. A “group”, just means “some other stuff”; usually it’s a bunch of carbons bonded to each other.

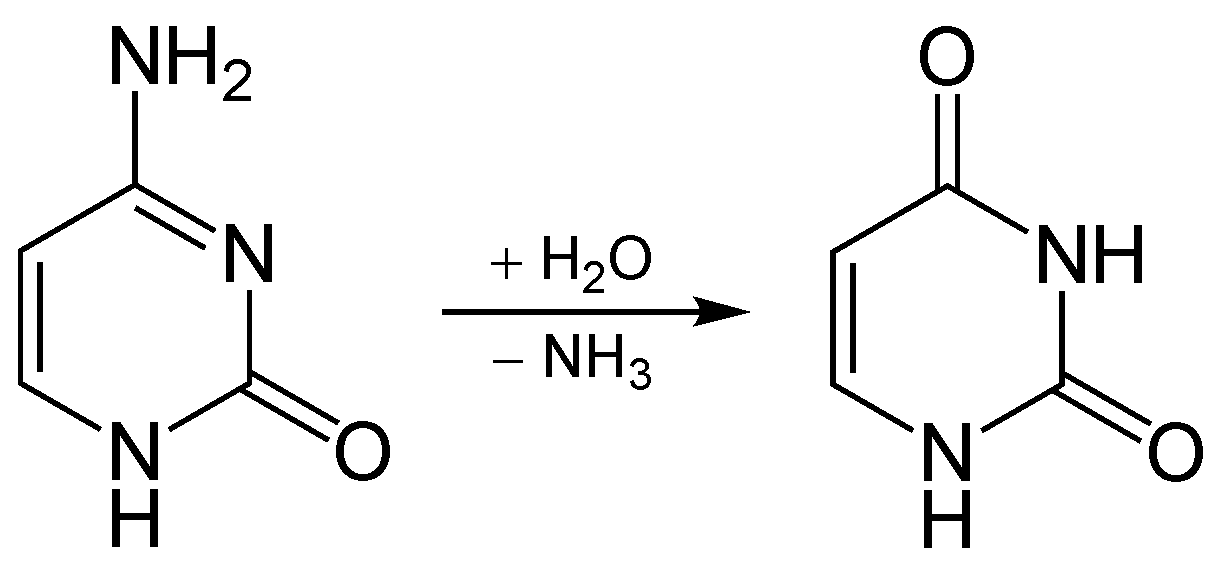

Normally, when cytosine deaminates in DNA, it becomes uracil. This reaction is shown below:

Cytosine deaminates to uracil

When this happens in cells, uracil is not a valid base for DNA, and other enzymes repair this mistake. Note that uracil is used in RNA as a substitute for thymine.

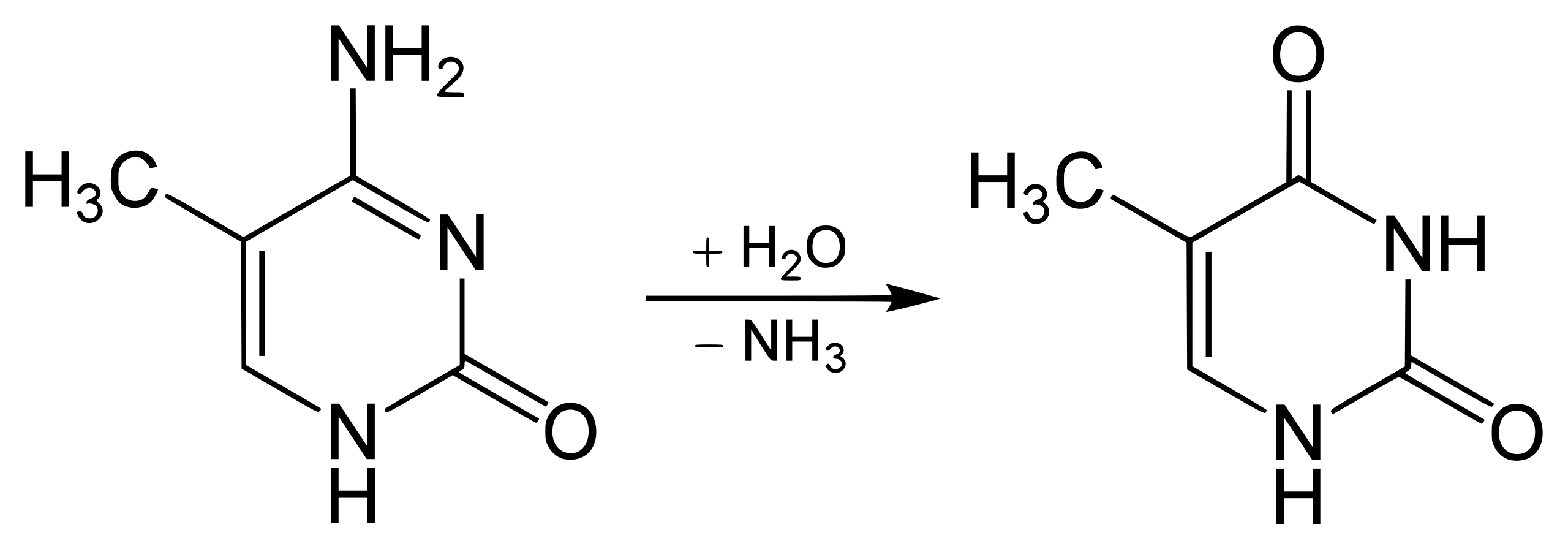

However, if the cytosine is first methylated (it has that extra carbon with the 3 hydrogen friends), then the reaction is different. Instead of becoming uracil, the cytosine becomes thymine. This reaction is shown below:

5-methylcytosine deaminates to thymine

Ok, this was a bit detailed, but it’s been useful for me to understand how little it takes to throw things out of balance in the biological world. In this case, you can see that the difference between these two reactions is pretty subtle.

However, the effect is profound. In the second case, the DNA now has an error in it. Rather than having a C that is paired with a G, there is now a T paired with a G. This is wrong (read: unstable), and there are now two possible outcomes for reparation. Either the T is “fixed” to match the G, and now we’re back to the original configuration, or the G is “fixed” to match the T. In the second case, a mutation has been introduced into the genome of the organism.

If the error correction produces a mutation several times, then genes can be turned on and off by this process. In an even more interesting case, if the genes that are being modified are passed to offspring, then now we have a mechanism for epigenetics. Genomes can be modified in living organisms, these mutations can be passed on to offspring. This is an area of research that has received a great amount of attention in the last 10 years.

Why would we care about these mutations in bacteria? Because we want the bacteria to do what we tell them to with the plasmids we transfer into them, and mutations thwart those efforts.

Protecting DNA

In prokaryotic cells, there is a system called the “restriction modification system”. The job of this system is to digest DNA. The difficulty is that the cell has a bunch of DNA in it called a genome that, you know, keeps it alive. A cell that digests its own genome does not produce offspring. So, somehow, there needs to be a difference between the genome of the prokaryote, and any foreign DNA. Interestingly, this operates as a kind of simplified immune system for the prokaryote. That differentiating factor is methylation.

There are actually 4 different kinds of systems that are used to differentiate host DNA from foreign DNA, and they range in complexity. I may write more about this in the future, but for now I will wave my hands and say that these systems are complicated, and they all require methylation.

Synthetic biologists need to care about DNA protection through methylation because plasmids are foreign DNA, and by default, e. coli will reject them by digesting them. There are two ways to overcome this, the first is to choose an e. coli strain that is deficient in the restriction enzymes that would digest your plasmids, and the second is to add a methylation enzyme into the plasmid so that it looks like native DNA to the e. coli.

Resources

As usual, this required a lot of wikipedia diving. The images here were obtained from wikimedia.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DNA_methylation

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/5-Methylcytosine

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Restriction_enzyme

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Restriction_modification_system

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deamination

- https://bitesizebio.com/30630/choosing-right-e-coli-strain/